Editor (Art)

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the then Party Secretary General of Vietnam became conscious of the damage brought by an economic system of large-scale production and centralised planning to Vietnam’s financial progress. Consequently, a long-term series of economic reforms known as the ‘Doi Moi’ policy was launched in 1986, and together with President Clinton’s decision to lift the U.S. trade embargo in 1994, led to Vietnam’s rampant economic ascension.

Described by many as a ‘leapfrogging’ process, the rapid increase in financial potential meant that the Vietnamese society became an avidly consumerist one. Embracing the ways of a West whose values they have long opposed and resisted — in a matter of decades — the Vietnamese faced a critical shift in values, be it moral, social or ideological. It is with this leap from an era to another and with the mutations it determined in every individual, that Vietnamese artist Hung Nguyen Manh started his journey in 2011.

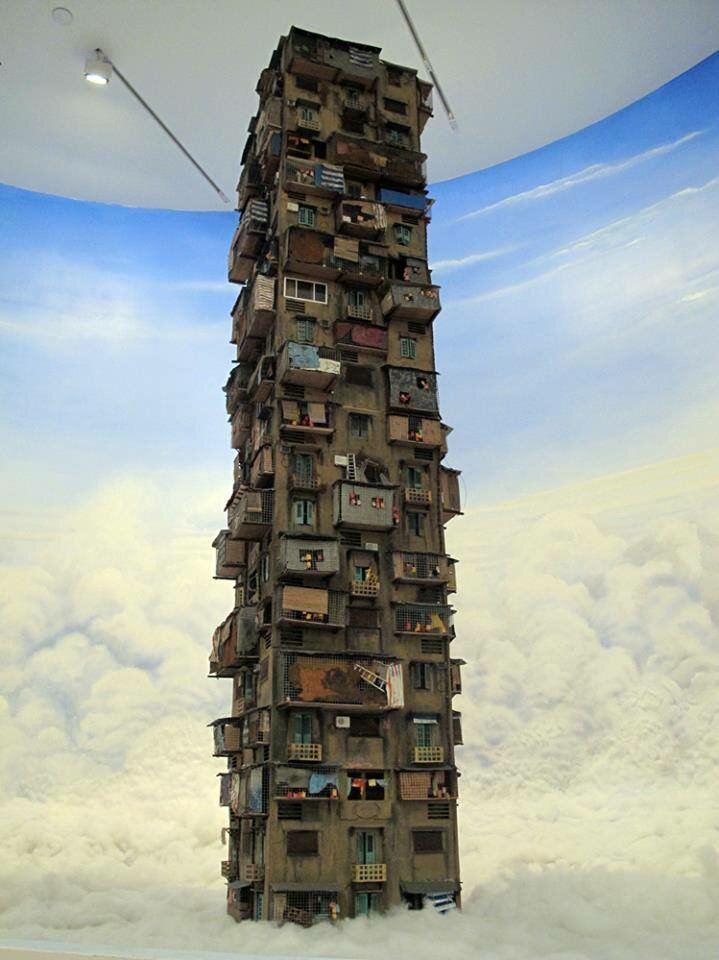

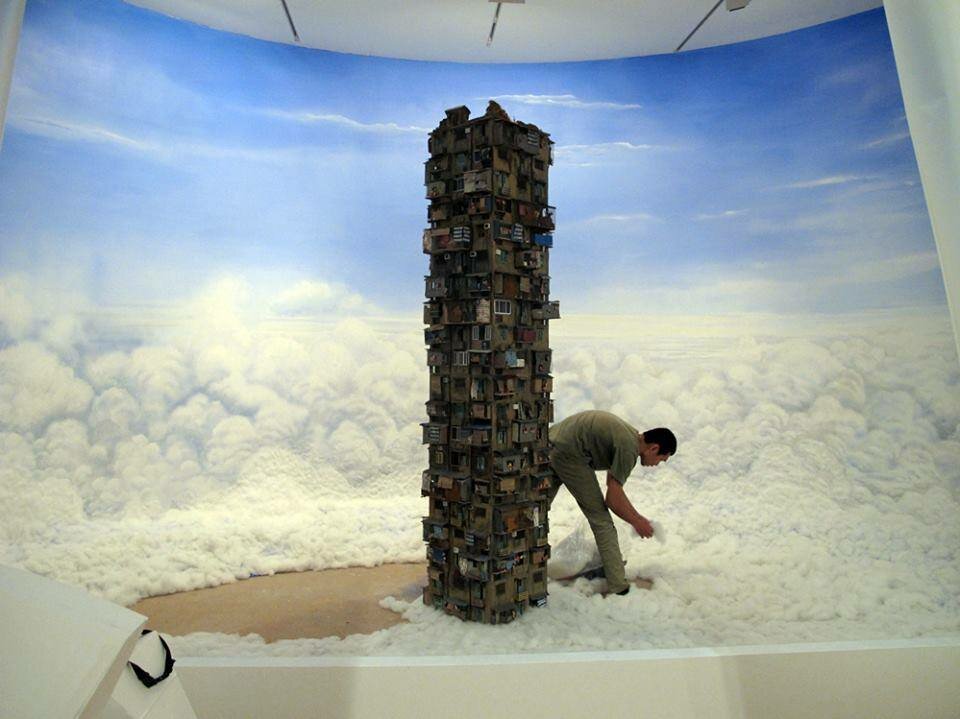

‘Living Together in Paradise’ is the three-meter high diorama sculpture of a Soviet-style residential housing-block and the artist’s childhood home. While the main structure of the tower was built using laser-cut technique, the details were modelled and attached by Hung, together with a skilled team of ten. Exposed at the 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Queensland, Australia, ‘Living Together’ represents the subjective, quasi-historical tale lived by the man and told by the artist. Patient and wise, Hung took the time to talk to us and cast light on the many questions surrounding his otherworldly art.

Through its positioning above the clouds, the diorama gains a mythological quality as if it were an ironic depiction of the mythical Mount Olympus. “I think that generally, all the myths created by human society share common elements,” says Hung. “They aim to reflect the society they are born within.” And what this sculpture reflects of the Vietnamese society is the stark contrast between, but also the cohabitation of the old and the new.

‘Living Together’ has the appearance of an old Soviet-style public-housing block, but the height of a modern sky-scraper. About this exaggerated height and the symbolic meaning it bears, the artist says it was meant to reflect the present state of affairs in Vietnam. “After so many years of financial hardship, we are now living in the latest modern constructions and indulge ourselves in consumerist pleasures that would have seemed impossible a couple of decades ago. Still, we are unsatisfied, always amidst perpetual building and rebuilding our living spaces, which is one of the most visible effects of the rapid economic boom that Vietnam has witnessed as of late. My aim as an artist was to criticise the unlimited greed of people, who are never satisfied with the lives that they live and the possessions they have. And as far as greed goes, it is a universal feeling.”

The present, however, is fundamentally different from the past, as the experience of living in a residential housing-block is not much like that of being the resident of a sky-scraper. About the first 20 years of his life, Hung talks fervently, with mixed nostalgia and indignation. “The block was built in the 1960s as a symbol of the success of Socialism and of the high purpose that state employees had to strive to reach,” Hung says. “A standard apartment was shared by two or three families, and if one family was assigned the kitchen, then the other took the bathroom. In the context of a difficult economy, with insufficient space to live in and with many deprivations, these families often had to expand their living space with whatever was possible, sometimes even with a cage! Also, most of them had to install their own water pumps and pipes, bring livestock or poultry into their apartments, grow vegetables or even do farming in the same apartments, only to improve their living standards. And it goes without saying that they were truly unsatisfied with the living conditions. When people are confined to such a limited space, it’s incredibly difficult to be nice to one another! Even though my family left the building in 1996, when I was 20 years old, I have witnessed too many arguments, conflicts, even fights, to the point that I wondered if angels could live together in Paradise.”

Hung traces the origins of his artistic stance back to his perspective on conflict. “My work is usually inspired by the conflicts that arise among people. I have found conflicts everywhere, from the small, isolated group of our community, to the country and the planet. Conflicts exist everywhere and inside everyone, so I see it as a natural fact that stems out of people’s differences. And as angels are different, they too have conflicts. Therefore, I made use of this state of isolation to send a message: that even the angels living in an otherworldly paradise can’t escape their community (Heaven), and so, they must face conflict.” The responsibility of whatever arises from human interaction, as suggested by the artist, should rest on the shoulders of each and every individual. As every community’s life is an experience all its members participate in, all of them must strive to keep it in balance across epochs, political regimes and economic systems — a Paradise all angels can live in.

Image Courtesy: © Hung Nguyen Manh

Andreea Saioc

Latest posts by Andreea Saioc (see all)

- Could Angels Live Together in Paradise? — A Conversation with Vietnamese Artist Hung Nguyen Manh - January 17, 2014

- Santa Strikes A Pose! ‘Santa Classics’ by Ed Wheeler - January 6, 2014

- ‘Reality Rearranged’ — By Tommy Ingberg - December 13, 2013

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.